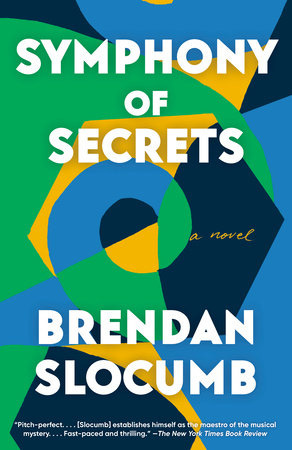

If you haven’t read Symphony of Secrets by Brendan Slocumb, prepare to be outraged. You know how some novels just hit close to the bone? My bookclub read it for the month of February, and the conversation with him was fabulous! (I’ll leave up the recording of our conversation on Instagram for just a few more days if you’d like to watch. Also, if you’re not already a member of my bookclub, you’re invited to join!) Slocumb’s novel is not based on a true story, but it may as well be.

In the novel, a (fictional) famous white composer Frederic Delaney claims to have created extraordinary music that was actually composed by a genius Black woman Josephine Reed in the early twentieth century. Delaney and his descendants make a fortune, while Reed’s North Carolina family never earns a penny or even knows that she ever composed.

In the present-day storyline, musicologist and professor Bern Hendricks and his longtime friend Eboni Washington are hired by the Delaney Foundation to transcribe a rediscovered manuscript. But soon they discover the deceit.

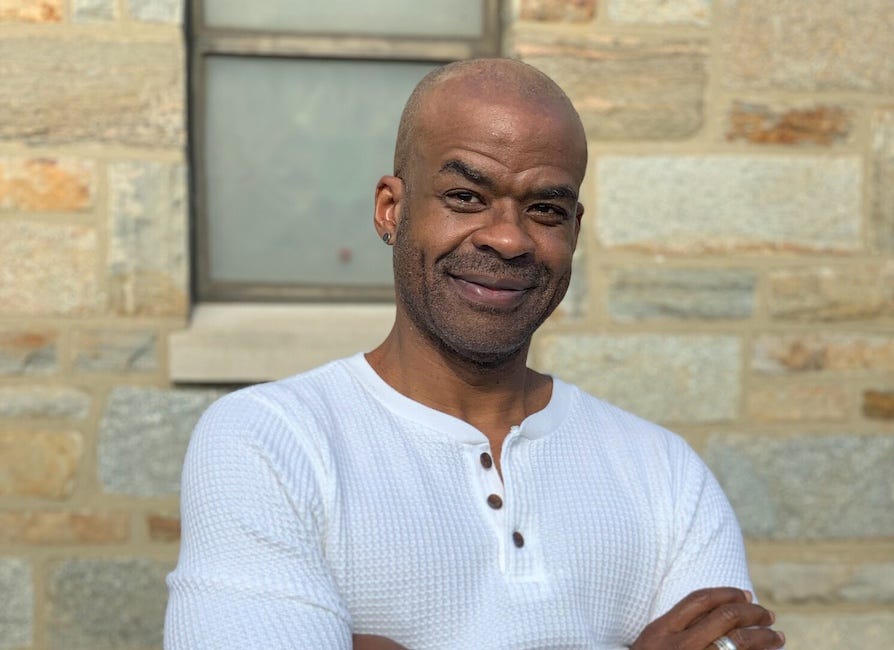

The novel goes back and forth between past and present, and let me tell you: it’s a wild ride! The author is a professional classical musician and this is his second novel. Y’all he is a major talent, and I’m so happy to welcome his voice into the writing world. I love the way he infuses his knowledge of music into the story. And he doesn’t talk down to us musical novices, y’all. He’s talking seventh chords and ii-v-i progressions. Beautiful stuff.

Slocumb also knows how to research history and craft a spot-on historical novel. Listen to my interview with him to hear how this vegan, classically-inspired musician-novelist writes a book in four months. Yup, you got it, the man is brilliant.

Now y’all know it’s the history part that always captures my imagination. I love it so much! In the spirit of Black History Month and now Women’s History Month, I thought I’d talk a little here about the history of Black women classical composers…

I first heard Florence Price’s name on a NPR story about the history of symphonies overlooking music by women composers. My ears perked up when it was reported that the Philadelphia Symphony had earned a 2022 Grammy with their performance of Price’s First and Third Symphonies. That was just four years after the 2018 season when the Philadelphia Orchestra did not perform work by one single female composer. Not only were they now playing women, but they performed work by an African American woman. And the music was good. Really good.

Price is the first African American woman composer to have a symphony performed by a major symphony orchestra when the Chicago Symphony Orchestra performed her work on June 15, 1933. Born in Little Rock, Arkansas to a successful dentist father and accomplished pianist and businesswoman mother, Price attended the New England Conservatory from 1903-1906. Despite her considerable accomplishments, Price’s life was complicated by Jim Crow and the racism of her era. The pianist Karen Walwyn has put together a fascinating biographical timeline here if you want to learn more about Price.

You can do your own YouTube digging, but here is a beautiful violin concerto composed by Price. Now get this: the concerto was discovered in the attic of an abandoned house on the outskirts of Chicago in 2009! Among these papers were Violin Concertos No. 1 and 2.

Apparently, a couple was preparing to demolish a dilapidated house that had been ransacked by vandals and damaged by a fallen tree when they discovered “piles of musical manuscripts, books, personal papers, and other documents” bearing Price’s name! They learned that the house had once been her summer home. Can you imagine discovering a treasure trove like that?

According to the above-referenced New Yorker article (which was published in 2018), it wasn’t hard to understand why Price went undiscovered for so long:

“In a 1943 letter to the conductor Serge Koussevitzky, she introduced herself thus: ‘My dear Dr. Koussevitzky, To begin with I have two handicaps—those of sex and race. I am a woman; and I have some Negro blood in my veins.’ She plainly saw these factors as obstacles to her career, because she then spoke of Koussevitzky ‘knowing the worst.’ Indeed, she had a difficult time making headway in a culture that defined composers as white, male, and dead. One prominent conductor took up her cause—Frederick Stock, the German-born music director of the Chicago Symphony—but most others ignored her, Koussevitzky included. Only in the past couple of decades have Price’s major works begun to receive recordings and performances, and these are still infrequent.” —by Alex Ross for The New Yorker, January 29, 2018

During my chat with Brendan Slocumb, someone in the bookclub mentioned Margaret Bonds, and I hadn’t heard of her, so I immediately began to do some research. Interestingly, her childhood was similar to Price’s. Both were daughters of pianist mothers and doctor fathers. In fact, Bonds actually studied composition with Price in Chicago, then went on to receive degrees from Northwestern University and study at Juilliard School of Music in NYC.

Bonds was the first African American to perform with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and composed dozens of pieces, including pieces for voice, piano, and stage. Musicologist John Michael Cooper has written a biography of Bonds which is forthcoming from Oxford UP. I love what he has to say about the differences between “rediscovery” of these artists and “recovery.”

“In order to be ‘rediscovered,’ something has to have first been ‘discovered,’ and in fact Margaret Bonds’s name, and the few of her compositions that the political economy of classical music did not actively suppress during her lifetime, have never really been forgotten. For example, her setting of He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands, first written for soprano Catherine Van Buren after the death of Bonds’s mother in 1957 and made famous by Van Buren’s student and Bonds’s friend Leontyne Price in 1962, remains the gold standard for that particular spiritual: there are other settings, but everyone always returns to Bonds’s. And her Troubled Water has been a mainstay of the piano repertoire, especially for the community of African-American pianists, since it was published in 1967. So this is more a matter of recovery than either discovery or rediscovery – that term is still a little fuzzy, but it comes closer than either of those other two to giving due credit to those who have acted as Bonds’s stewards over all these years.” — John Michael Cooper

Tragically, Margaret Bonds reportedly passed away due to a heart attack at age 59.

Okay, now those of you who know classical music will surely understand how absolutely stunning this piece is by composer Julia Perry. I can’t stop listening to it.

Born in 1924 in Akron, Ohio, Perry received degrees at Westminster Choir College where she studied piano, voice, and composition. Like Bonds, she also studied at Julliard. Perry received two Guggenheim Fellowships which allowed her to continue her studies in Europe. Her works were performed by major symphony orchestras to great critical acclaim. Like Slocumb’s fictional Josephine Reed, Perry incorporated African American musical language such as blues and spirituals into her compositions.

By the time of her untimely death at age 55, Perry had composed three operas, fourteen choral works, and twelve symphonies. Perry’s talent was remarkable, and I wish more people knew her name.

There are others, too. Undine Smith Moore (1904-1989) was often called the “Dean of Black Women Composers.” The granddaughter of enslaved people, her work often incorporated spirituals.

Nora Douglas Holt (1884/5-1974) graduated valedictorian of her college class and went on to have a successful career as a composer and performer that spanned continents. Holt composed more than 200 works of chamber and orchestral music.

Both of my daughters are classical pianists, and I hope to introduce some of these works to them. It really does matter to us fans of classical music to have these women’s work included in conversations about twentieth century composers.

Now see what literature can do?

I am so grateful for this post. As an African American woman who was introduced to classical music as a 4th grade in a segregated school, I am pleased and blessed to learn about these composers.

Okay, of course I love this post, as there is so much to say about Black classical music history. Much of it is, unsurprisingly, not pretty, and tragic and infuriating in the white establishment's attempts to crush it. Here's my Washington Post review of a book called Dvorak's Prophecy, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/he-saw-a-noble-future-for-black-and-indigenous-composers-he-was-wrong/2021/12/08/9705c2f4-2ba1-11ec-985d-3150f7e106b2_story.html, which tells the story of Bohemian composer Dvorak predicting that the future of American music was Indigenous, by which he meant both Black and Native American, and the lengths he went to try to make that happen, and the attempts at erasure by well known musicians whom history has coddled. Can't resist sharing. It's a big topic.